Osteoporosis

Osteoporosis (sometimes known as “Brittle Bone Disease” or “Brittle Bones”) means ‘porous’ bones, and it is the single most important health hazard for women past the menopause – it is more common than breast cancer, heart disease, stroke, or diabetes.

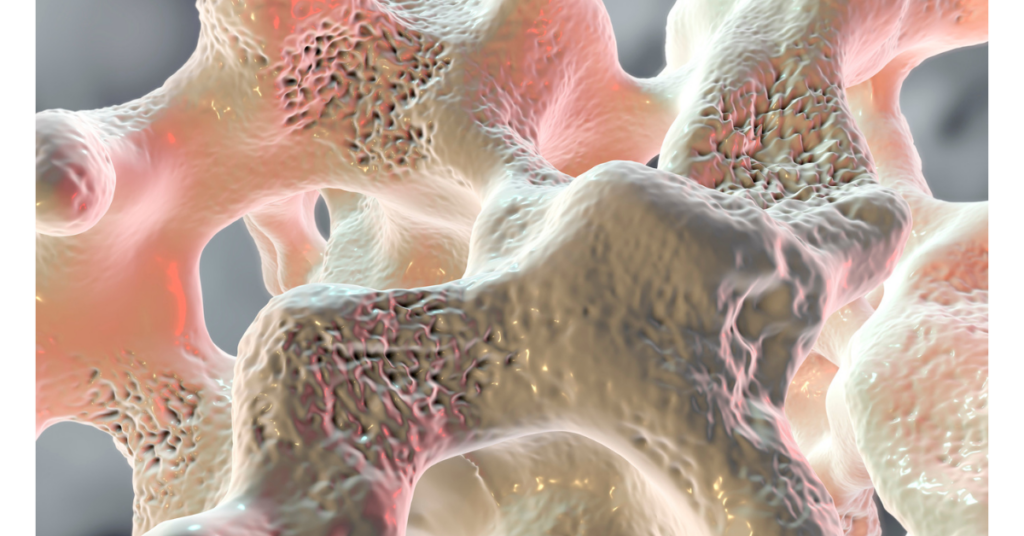

Healthy bones have a thick outer shell, a strong inner mesh filled with collagen (protein), calcium salts and other minerals, and blood vessels.

The inside looks like honeycomb, with the blood vessels and bone marrow in the spaces. Osteoporotic bone has a thinner, weaker outer bone layer and a weak porous core with reduced calcium and fewer blood vessels.

Bone constantly regenerates itself

Cells known as osteoclasts trigger bone resorption, while cells known as osteoblasts lay down new bone (calcium and phosphate) at the site of the old bone.

Controlled mainly by the hormone oestrogen, this constantly ongoing process helps maintain the human skeletal structure.

Unfortunately, as we age, the work of the bone-building osteoblasts begins to slow, while the osteoclasts continue to breakdown old bone structure at virtually the same pace as before. Eventually, the bone can become so weak and brittle that it fractures upon impact, even after a mild bump or fall. Like wrinkling skin, this change generally proceeds very slowly, corresponding with the normal ageing process.

But in a certain percentage of individuals, the bone loss process seems to be accelerated, with some individuals losing as much as 1% or more bone density every year after reaching middle age.

Scientists estimate that the risk of fracture doubles for every 10% bone density loss

Osteoporosis affects both men and women with approximately 46% of all vertebral fractures in men attributable to secondary osteoporosis.

Women are more vulnerable to osteoporosis due to both starting with a 30% lower bone mass than men at maturity, and suffering with the sudden decrease in oestrogen production during menopause.

Oestrogen modulates bone metabolism by enhancing osteoblast bone formation and inhibiting osteoclast bone resorption, thereby maintaining bone density. Increased osteoclast resorptive activity is believed to arise from the loss of the oestrogen-dependent repression of interleukin 6 (IL-6) levels.

There are two factors that may determine the onset of osteoporosis in women. Peak bone mass at the onset of menopause and the rate at which bone density is lost after menopause. For both men and women, the onset of osteoporosis can be mediated by:

- Taking regular exercise (such as vigorous walking, running, dancing, tennis).

- Including dark green vegetables such as broccoli, spinach, watercress, and spring greens in your diet – as these are rich in calcium – and are a safer and healthier option than dairy sources. In fact, a plant-based diet reduces the risk of osteoporosis in older adults

- Maintaining vitamin D levels – essential to absorb calcium. The major source is from sunlight on skin, and 15-20 minutes a day on your face and arms during summer is adequate for the body to store enough to last the rest of the year. Vitamin D can also be obtained through your daily diet.

- Not smoking. Smoking has been shown to decrease circulating oestrogen concentrations.

| Suggested Daily Calcium Intake | |

| WOMEN |

|

| 50-64 years(postmenopausal with estrogenic supplements) |

1,000 mg |

| 50-64 years(postmenopausal without estrogenic supplements) |

1,500 mg |

|

65+ years |

1,500 mg |

| MEN |

|

|

25-64 years |

1,000 mg |

|

65+ years |

1,500 mg |

For women to more fully compensate for the changes brought about by age, an improved diet must be accompanied by supplementing or boosting hormonal activity.

Traditionally this would be by using conventional HRT, but effective alternatives are available, meaning the health risks associated with long term use of conventional HRT need not be taken.

For oestrogen maintenance and menopausal symptom control, explore Natural HRT, Phytoestrogens, Red Clover, and Conventional HRT.

Exercise

Exercise plays a crucial role in both preventing and managing osteoporosis. Weight-bearing exercises, such as walking, jogging, and resistance training, help stimulate bone formation by encouraging the body to produce more bone tissue, thereby increasing bone density.

Regular physical activity also enhances muscle strength, balance, and coordination, which are essential in preventing falls that can lead to fractures in people with osteoporosis. Moreover, exercise improves circulation and joint flexibility, which supports the healing process in those already affected by the condition.

By incorporating consistent exercise into daily routines, individuals can significantly reduce their risk of developing osteoporosis and enhance their body’s ability to recover from it.

References

Daniell HW. Osteoporosis of the slender smoker. Vertebral compression fractures and loss of metacarpal cortex in relation to postmenopausal cigarette smoking and lack of obesity. Arch Intern Med. 1976 Mar;136(3):298-304. doi: 10.1001/archinte.136.3.298. PMID: 946588.

Osteoporosis: Review of the evidence for prevention, diagnosis and treatment and cost-effectiveness analysis. Executive summary. Osteoporos Int. 1998;8 Suppl 4:S3-6. PMID: 10197172.

See Also

National Health Association on Osteoporosis https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/osteoporosis